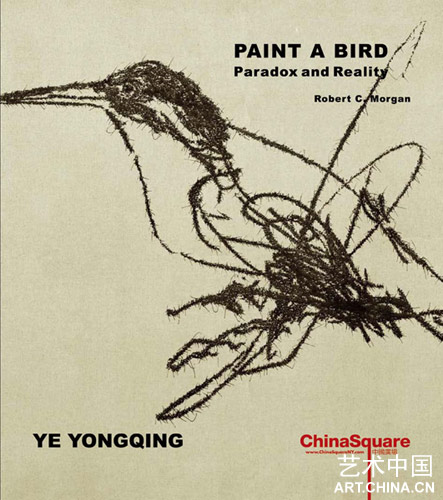

葉永青首次紐約個(gè)展《畫鳥(niǎo)》在中國(guó)廣場(chǎng)開(kāi)幕

畫鳥(niǎo):矛盾與現(xiàn)實(shí)

2008年5月1日(紐約時(shí)間),在紐約中國(guó)廣場(chǎng)藝術(shù)空間舉辦了藝術(shù)家葉永青先生的首次紐約個(gè)展《畫鳥(niǎo):矛盾與現(xiàn)實(shí)》,葉永青以及夫人甫立亞一同出席當(dāng)天晚上的開(kāi)幕酒會(huì)。酒會(huì)上新老朋友歡聚一堂,紐約藝術(shù)界的重要評(píng)論家策展人幾乎全部到場(chǎng)。

葉永青作為西南藝術(shù)群體的創(chuàng)始人之一,早年與張曉剛,毛旭輝等一起組成了西南當(dāng)代藝術(shù)群體,在早期沒(méi)有畫廊和學(xué)術(shù)機(jī)構(gòu)支持的情況下,在荒蠻沒(méi)有喝彩和生活來(lái)源的藝術(shù)領(lǐng)域中拼殺出一條道路。

作為西南藝術(shù)群體代表人物之一,人稱“葉帥”的葉永青才逐漸從這個(gè)群體里的“領(lǐng)路人”——策展人和介紹海內(nèi)外收藏家給西南藝術(shù)家們的角色,慢慢回歸到純粹的藝術(shù)家身份。雖然說(shuō)在藝術(shù)家被瘋狂追逐的今天,紅火的藝術(shù)家們仿佛要被各種需求從精神上到藝術(shù)上榨干,要把自己留在畫室里不是一件容易的事情,但是葉永青做到了。從今年四月香港的回顧展,CIGE2008展出的作品,以及這次在紐約的首次個(gè)展不難看出,葉帥的作品《鳥(niǎo)》系列已經(jīng)有了更多更新的演變,色彩和構(gòu)圖上也更趨年輕充滿活力。

紐約中國(guó)廣場(chǎng)從去年開(kāi)始籌劃葉永青個(gè)展,早在去年年底葉永青的三幅重要作品已經(jīng)悄悄運(yùn)送到紐約,《典藏》雜志國(guó)際版《Yishu》五月封面采用了葉永青的作品,并在內(nèi)文用大量的篇幅進(jìn)行介紹,可見(jiàn)對(duì)其藝術(shù)成就相當(dāng)肯定和重視。中國(guó)廣場(chǎng)為葉永青請(qǐng)到重要藝術(shù)評(píng)論家和策展人:羅伯特.摩根(Robert C. Morgan ),策展人對(duì)葉永青的作品非常喜歡。

羅伯特·摩根說(shuō):葉永青以其細(xì)膩且深賦詩(shī)意的筆觸,為他筆下的鳥(niǎo)織合出一個(gè)夢(mèng)境和神話精妙地與現(xiàn)實(shí)共存的場(chǎng)景。他用連綿針毫細(xì)細(xì)勾勒,重現(xiàn)制造出如同將信手拈來(lái)的速寫圖像放大般粗曠的質(zhì)感,一只只栩如生的飛禽,在這般看似傳統(tǒng)卻又新穎的技法中呈現(xiàn)。或飛或棲,葉縝密地閱讀觀察他們的姿態(tài),并以此融合古今沖突的表現(xiàn)手法,捕捉畫中鳥(niǎo)兒的身影。如同書畫的筆墨,鳥(niǎo)的神色氣韻在針筆細(xì)細(xì)堆砌間,悠然流暢于畫布之上;然而他堅(jiān)韌卻細(xì)碎的筆觸,卻又與傳統(tǒng)文人畫大相徑庭。他筆下的生物,既優(yōu)雅又豪邁,極其壓抑自制卻又十分天馬行空。其中一收一放,將向來(lái)在西方神話中被視為具靈性象征的鳥(niǎo)類,再度展翅歸溯到一個(gè)神人相遇的場(chǎng)域之中。

葉永青1958年生于昆明,畢業(yè)于四川美術(shù)學(xué)院。在其藝術(shù)生涯中,展覽遍及中國(guó)重要城市以及歐美各地。《畫鳥(niǎo):矛盾與現(xiàn)實(shí)》為葉永青暌違美國(guó)十八年后,于紐約再次發(fā)表新作。此展展至2008年5月30日。

藝術(shù)家楊識(shí)宏,

策展人 Robert C. Morgan

藝術(shù)家Situ Qiang

模特

Alex Cao

葉永青

批評(píng)家Ggerarg Hagerty和甫立亞

Ye Yongqing’s

Paint A Bird: Paradox and Reality

Robert C. Morgan

“I often see my life as like that of migratory bird moving among several different cities, fragmented and with no fixed abode. I paint and put together my creations the same way: I hit one target and move on.”

Ye Yongqing

(letter to Li Xianting, 1991)

My first reaction to the paintings of Ye Yongqing was a spirit of kinship with his ironic bird paintings. They expressed a kind of paradox between the ambiguous structure of the representation and a keen intensity in the deliberation of the lines. I sensed some kind of agreement in terms of the way he understands art, not so much in the theoretical sense, but in the spirit of the forms. His formal process of painting over the projection of scribbled birds retained a child-like simplicity and a profound stylish demeanor. They resemble indirectly the work of the Bauhaus artist Paul Klee in that they appeared to exist outside of any pretension. They transmitted a kind of liberation, a freedom from the restraint of academic art or trendy magazine art. They offered a confession of an inner-struggle. I have always respected the inner-struggle of artists, although, as the poet Yeats concluded, this is difficult to define in anyone other than oneself. But there is a kind of emulation is possible, as when artists identify with similar thoughts and feelings, not from the point of view of academic textbooks or theoretical jargon, but from the direct experience of the work itself.

I have never accepted the notion that cultural difference is a barrier in terms of understanding the truth in art. In recognizing the term “truth of art’ is also problematic. It carries implications associated with theosophy and utopia in early Western Modernism. Because of this, there is an underlying suspicion of anyone who would claim to recognize the truth in an artist’s work. This widely held cynical belief is unfortunate, because it represents the power of conformity, mob rule, enforced consensus over democratic thinking. How can a culture exist in any profound or positive sense when there is no common acknowledgement of truth – neither in the political nor ideological sense, but even in the sense of feeling the directness of experience? This kind of directness of experience in art is highly underplayed and misunderstood in recent years. Through the work of Ye Yongqing one can get a handle on the painter’s truth, not as a pretension or ostentations system of belief, not as a circumscribed manner of dealing with one’s reality, but as a means toward independent thinking, a way of feeling a subject that connects to the power of thought and to the dignity of values that represent human endurance, compassion, and emulation.

The symbolic motif of the bird and the likeness of human beings to birds – these are common themes that have occurred not only in Chinese art, but throughout the history of Western art as well. The Flemish painter Bosch painted bizarre phantasmagorical bird-like humans, presumably as a fantasy or dream world vision that served as a testament to the hypocrisy of morality in the sixteenth century. This is very probable, if not verifiable. Moral hypocrisy has been sublimated in art for centuries in the era of Pompeii, in the Persian miniatures, and in courtly scenes from the early Han Dynasty. Hypocrisy is the painter’s means whereby the truth of morality reveals a different face, an uneven countenance, a way of seeing that is unclear and irredeemable on its own terms. Ye Yongqing’s “Paint A Bird” series, which began in the 1990s, is a clear example of searching through the hypocrisy of Chinese Confucianism in the era after the Cultural Revolution. One might say that Ye Yongqing has taken a more indirect route than many of the “cynical realists” whose symbolism is either too superficial or symbolic in the weakened sense of failing short of true allegory. Ye Yongqing’s “Paint A Bird” series carries the elegant absurdity of a critique, a humble dissociated critique, yet still retains a message that is unforgettable, one that is worthy of further investigation and interpretation.

Whereas the “Big Poster” series carries a semiotics of signs and symbols from Chinese history in the second half of the twentieth century, the format may have been partially inspired by the “combine” and silkscreen paintings of Rauschenberg whose work Ye Yongqing had seen in the mid-eighties. Although Li articulated a position insisting on the differences between Eastern and Western aesthetics, the formal resemblances of his paintings at that time hold some proximity to those of Rauschenberg. In many ways, the impact of the American Neo Dadaist exhibition offered a spur for Ye to advocate a rough traditional style of painting on old calendars, wall posters, and newsprint, and thus to reveal the internal symbolic aspects of his imagery with a new formal apparatus. Still, there is little doubt that the propaganda imagery designed during the Cultural Revolution directly influenced a reaction on the part of the artist in the “Big Posters”.

Even so, Ye Yongqing is not the type of artist who will be satisfied to stay in one place doing one thing for very long. By the year 2000, he began his “bird paintings” – perhaps the most significant series of work to date. The “birds” are both original and confrontational, both significance and unruly, sinister and celebrative, ambiguous and illuminating in that they contain the allegorical apparatus to constitute a point of view that is truly Chinese. First of all, these magnificent paintings play with the apparatus of the gesture, the painted line that is scribbled, or impulsively scrawled on the surface, without any misgiving. In fact, the structure of these painting depends not only on the scribbling but on a heightened visual articulation of the line within the scribble. There are numerous examples from “painting a bird” to the “big pigeon,” from the “wound” to the “heartbreak,” or from the “posture” to the “birdcage.” All of these motifs rest upon a single intention -- the supreme motivation of tricking the eye into thinking that the gesture was made quickly, impulsively, and without forethought. The complexity of the idea suggests that the original sketch or scribble was in fact made impulsively, but then Ye takes the scribble to a second a third level of power. We begin to understand that over the stained effects on the beige surface of the canvas are these tiny quick hair-like strokes made quickly and fastidiously as Ye goes over the projection of the line, darkening areas of the surface to build up a contrasting dimensionality in relation to the bird’s physiognomy, the tail feathers, the wings, the beak, and the claws. Everything is accounted for in the interstices between the volumetric shape of the bird and the scribbled lines that intercede.

Ye Yongqing is an artist who has struggled with his social and psychological dilemma as an artist through most of the eighties and into the nineties. This struggle is clear in his early paintings, whether figurative or non-figurative. His mood in transmitted through the darks and lights that encompass the space. There is an expressionistic tonality in the early paintings of the eighties, an excitation that grips the retina and pulls the eye inward toward the mind and heart, so that the eye was not only perceiving both thinking and feeling interactively with the signs on the surface. The “big poster” series of the nineties could be interpreted as the means by which the artist was able o pull himself out of despair and out of the conundrum that so many Chinese artists felt after their delusion with the events at Tiananmen Square. These artists included his companions in the Southwestern Art Group, such as Mao Xuhui, Pan Dehai, and Zhang Xiaogang. In 1991, his letter to the exhibition organizer and critic, Li Xianting, cited at the beginning of this essay, may be read as an affirmation of his desperation at that time. As a deeply committed Chinese artist Ye Yongqing believed he must transcend the limits that his society offered him. He must proceed with his art as a course of survival. The colorful grid paintings that followed the “big posters” in 1996 allowed a certain release from this despair. Although Li Xianting felt, in retrospect, that these paintings were too close to the Haitian-American painter Jean-Michel Basquiat, they served an important interior function for Ye between the “big posters” and the beginning of the so-called “Paint A Bird” series in late 1999-2000. Through the birds paintings Ye Yongqing came back to life by discovering a new kind of ironic distance by opening the threshold of Chinese painting to a simultaneous view of both the past and the future.

In this sense, Ye Yongqing found himself working squarely in the present.

There can be little doubt of Li’s achievement with this series of work. He has managed to question the expressionist experience in painting through inserting a double of what the eye believes to be real. What we think we are seeing is not actually what is there, but, on the other hand, what is not there is the basic structure upon which the illusion has been created. This is Ye Yongqing’s brilliant tactic in that it allows him to express images in space through a process of instant negation. Hence, the power of the yinyang is omnipresent through expressionist assertiveness and instant cancellation. The literal point of his small brush and the extraordinary time and patience that it takes to follow the projection of lines on his canvas in not simply an act of meditation. What comes into view is a double illusion that goes beyond the linguistic Surrealism of the Belgian painter Magritte. It is not just that Ye Yongqing is drawing a bird partially concealed by expressive marks, but that the construction of the marks subverts the very presence of the image we thought we saw. In the traditional sense of tenth century Northern Song landscape painting, this is the mystery that makes those ink paintings so great. The illusions within nature are impossible to catch. They are either suspended or fleeting before our eyes. Just when we think we have it, the illusion doubles upon itself and makes us question the very basis of our knowing. We are stranded without an empirical reality. We are lost in space, yet rejuvenated by the absence that we believed was once present.

___________________________________________________________

Robert C. Morgan is an international critic, artist, curator, and lecturer who lives and works primarily in New York City. An author of many books, catalogs, and monographs on contemporary artists, Professor Morgan is focused on the problems of the artist in an era of globalized change and renovation. He holds both an advanced degree in Sculpture and a doctorate in contemporary art history, and currently lectures at Pratt Institute and the School of Visual Arts in New York.

|